︎HOME

Serpentine Galleries: Restauro Dinner

Click for artist's speech at the dinner

![]()

"Modern crop and livestock farming is the human activity that impacts and transforms the planet the most, affecting biodiversity, compacting the soil, polluting rivers and clearing forests. The Restauro [Restoration] (2016) project raises questions about the development of eating habits and their relationship with the environment, landscape, climate and life on earth. The work operates as a restaurant, in partnership with Vitor Braz, whose menu, prepared with the nutritionist and chef Neka Menna Barreto and the Escola ComoComo de Ecogastronomia in São Paulo, prioritizes the diversity of the plant kingdom originating in agro-forestry. This space for nutrition proposes a metabolic and digestive experience that is both physical and mental. Its ambience, carried out in partnership with O Grupo Inteiro, emerged from the idea of microclimates. The audios connected to the work were made by Marcelo Wasem, mainly in agroforests, where you can perceive another moment in the life of the foods that are brought for our consumption. Restauro encourages awareness about how we use our land and the global consequences of our choices. By understanding our digestive system as a sculptural tool, diners become participants in an environmental sculpture in progress where the act of nourishing oneself regenerates and shapes the landscape in which we live".

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Serpentine Galleries: Restauro Dinner

Click for artist's speech at the dinner

"Modern crop and livestock farming is the human activity that impacts and transforms the planet the most, affecting biodiversity, compacting the soil, polluting rivers and clearing forests. The Restauro [Restoration] (2016) project raises questions about the development of eating habits and their relationship with the environment, landscape, climate and life on earth. The work operates as a restaurant, in partnership with Vitor Braz, whose menu, prepared with the nutritionist and chef Neka Menna Barreto and the Escola ComoComo de Ecogastronomia in São Paulo, prioritizes the diversity of the plant kingdom originating in agro-forestry. This space for nutrition proposes a metabolic and digestive experience that is both physical and mental. Its ambience, carried out in partnership with O Grupo Inteiro, emerged from the idea of microclimates. The audios connected to the work were made by Marcelo Wasem, mainly in agroforests, where you can perceive another moment in the life of the foods that are brought for our consumption. Restauro encourages awareness about how we use our land and the global consequences of our choices. By understanding our digestive system as a sculptural tool, diners become participants in an environmental sculpture in progress where the act of nourishing oneself regenerates and shapes the landscape in which we live".

Interview with the journalist Marília Miragaia in August 2016:

Today, many authors, like Michael Poland and Alice Waters, make the case for seeing food as a political act. How does your work relate to this movement?

Jorge Menna Barreto: I follow Michael Poland and Alice Water’s work enthusiastically and I’m interested in approaching the act of eating as a political act. The issue of environmental impact sets the tone of the work I’m showing at the Biennial. Restauro is a form of political activism, yes, but more specifically, of food activism. I have researched agroforestry, agroecology, veganism and nutrition. I also have an academic career: I’m assistant professor at Rio de Janeiro State University where I teach sculpture and have outreach research programme called Contextual Consciousness: Between the Artistic and Environmental. In 2014 my postdoc studies looked at the relationship between art and agroecology, where I deepened my research into agroforestry and food activism.

How can Restauro lead viewers to question their relationship with food and the choices they make around food? Why transform a restaurant into an artwork?

JMB: Restauro operates through suggestions rather than statements. Like any poetic process, it doesn’t attempt to speak in the name of a given truth, but rather suggests another way of looking at the world. The concept of participation is very important to us. In our society, food is mainly seen as merchandise, which means our relationship with food is one with the food industry. It being a product often obscures food’s multidimensionality, so we stop paying attention to how it was produced, its history and complexity, in order to reduce it to its taste, texture, packaging and the pleasure it gives our taste buds. We are talking about a moment of consumer satisfaction, rather than a complex relationship that involves every facet of food. Part of the challenge of Restauro is to break down our visitors’ condition as consumers for them to see themselves as participants in a process beyond the act of eating that involves taste, satisfaction, pleasure—but without removing the relationship between food and its environmental impact. We know that farming today is the one human activity that most impacts the planet, so decisions about food based solely on taste are dangerous and compromise life on our planet. One of art’s most important roles is to create new images, or make existing ones more complex. So Restauro suggests that we redesign our digestive system for it to start not in the mouth, but in the earth. One of the images we’d like to create is visualizing food within this wider sphere. We’re not transforming a restaurant into an artwork, but expanding the concept of the restaurant for it to be an artwork as well. Restauro aims to lessen food’s role as an intermediary with industry, in order to increase its role as an intermediary between society and the environment. It’s interesting to pay attention to the word restaurant. we arrived at Restauro through its etymology. But the concept of restoring is linked to the individual. We go to a restaurant to restore ourselves, to recharge our energy and to feed ourselves. Restauro’s aim is for this restorative activity to take on a new scale. As well as restoring individually, we hope that taking part in the work will mean the hunger of visitors to the Biennial also helps regenerate the soil, maintain biodiversity, depollute our rivers, preserve forests and construct fairer relationships between farmer and consumer.

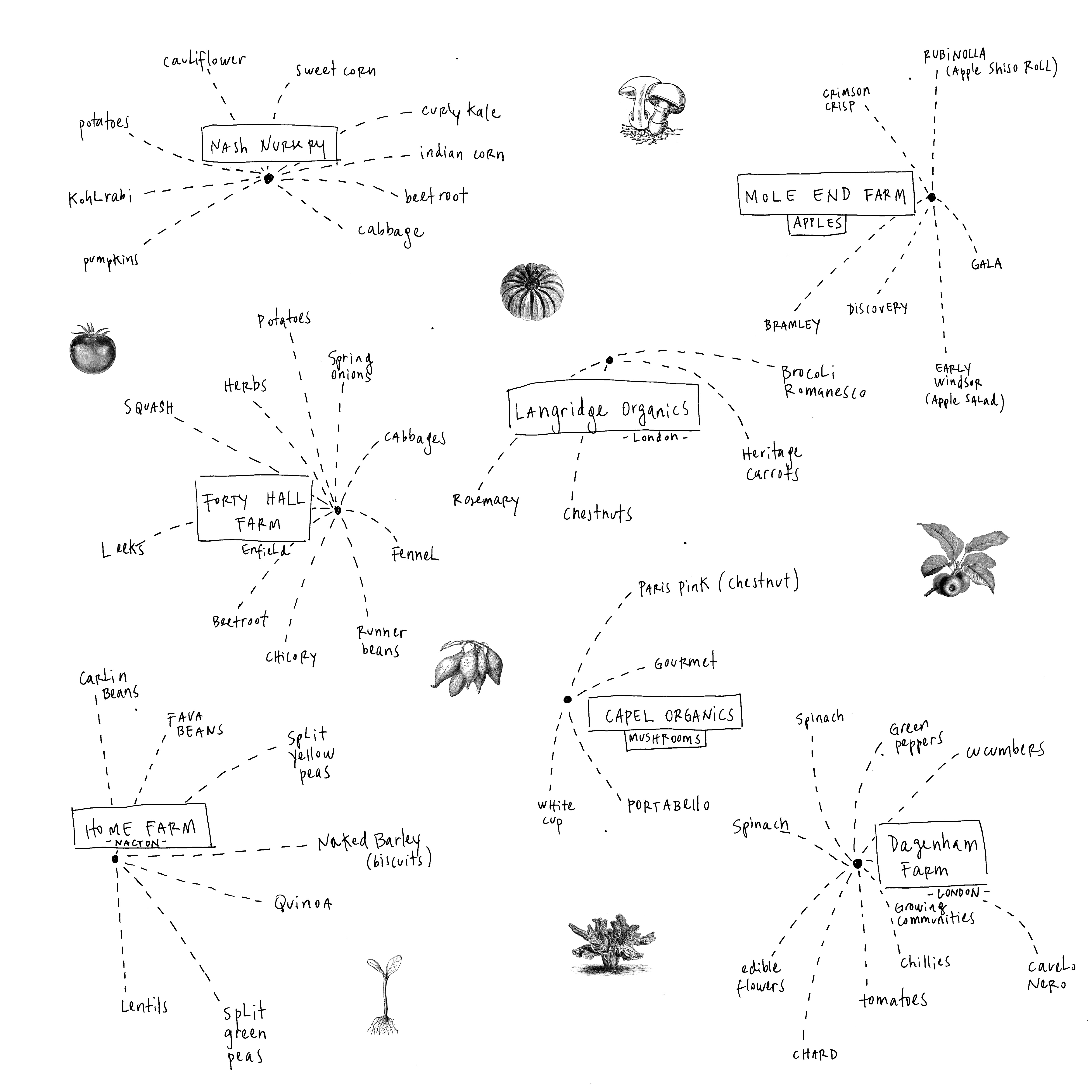

Tell me more about the preparatory work for “Restauro”. The project has partnerships with organic and agroforestry farmers, as well as with systems dedicated to recovering soils and biodiversity. How and why did you choose them? What is your relationship with them?

JMB: It’s worth mentioning that one of our partners, the São Paulo State Environment Secretariat (SMA), had a funding call for farmers wanting to grow food with agroforestry systems that supports initiatives to raise farmers’ awareness about the environmental impact of what they do and the important role that regenerating the environment has. The project’s called Microbacias II. While researching Restauro, we visited a network of agroforestry farmers set up mainly through this cooperation with the SMA. It was a pleasant surprise to find out about the SMA’s interest and, when we spoke, we realized we had similar goals. I think it’s interesting that we’ve found an ally in the Environment Secretariat, and not with the Agriculture and Produce Secretariat, for example. In some ways, it says a lot about the project. We visited around ten agroforestry farmers in the state, linked to the landless workers movement. They will be Restauro’s suppliers. We have weekly meetings here for farmers to meet the public, when the farmers bring their produce to supply the restaurant. This exercise short-circuits the farmer–consumer relationship and is one of the best things that organic markets have done, for instance. If you shake a farmer’s hand, you’re also creating a relationship with the earth that hand has worked. By supporting these farmers directly, we move away from a system that’s often perverse and obscures its sometimes irreversible, environmental impacts.

Did you make visits? You also made recordings of the agroforestry and monoculture plantation ecosystems, right? What did you intend to do and what did you discover?

JMB: We called the visits we made to agroforestry farmers “listening and mapping” exercises. In this section of the project, we worked with the artist and musician Marcelo Wasem. The idea was to arm ourselves with sound recording equipment to document both the sonic landscapes and statements from people working the land. In a forest, vision doesn’t count for much. Forests are dense environments the eyes can’t penetrate. Perhaps hearing is the most important sense to navigate through an environment of dense vegetation. When we asked a Native Brazilian if he’d seen a jaguar, he replied: if I’d ever seen one, it would be too late. In forests, each species has its own acoustic signature and occupies its own frequency. Twice a day, at dawn and dusk, there’s a party in the forest when species communicate amongst themselves, creating a huge web of sound that functions as a form of self-recognition and maps out possible mates, threats, predators or prey. The greater the biodiversity, the denser the forest’s symphony. There are studies that measure forest biodiversity and compare them with agroforests, which are the forests with the greatest human presence. It’s known that agroforests are more biodiverse than spontaneous forests, deconstructing the idea that excluding humans from jungle areas is the most useful environmental restoration strategy. Agroforestry includes man as a catalyst in forest processes, producing more food and speeding up the process of soil regeneration. The agroforester is a sculptor who decides where the sun’s rays fall and therefore organizes crops that don’t just serve humans, but all the forest’s inhabitants. It creates a system “warmed” by the human presence, who fulfils a role of mediating between species, reading each species’ abilities and talents, and managing how they interact by pruning. We set out to look for biodiversity, recording its sound and we also aimed to interview farmers in the forest, suggesting that the human voice is part of this symphony. In general, agroforesters don’t agree with the concept of environmental preservation areas that exclude man from nature. To our surprise, travelling around São Paulo state, the agroforests we visited were tiny islands in veritable monoculture seas of mostly sugarcane and eucalyptus. Then we decided to test our hypothesis and stopped in some monocultures to record the sonic landscapes present there. I’ve never heard such a deep, heavy silence. There are no birds, insects, animals or sounds of any other form of life. Monocultures are veritable deserts that exclude everything except that plantation’s sole focus. They eliminate biodiversity and the sonic landscape reveals how serious the situation is. It’s even sadder to know how this biodiversity is eliminated by pesticides and heavy machinery, which causes even more environmental damage. How much are we responsible for this and how do our habits encourage farming like this?

A diet based on plants alone might sound like a challenge to many viewers. How do you address this in the work?

JMB: The expression “on plants alone” isn’t right. We have more than 25,000 edible plant species on the planet and just five make up 70% of our diet (corn, sugarcane and wheat are among them). When we go into any old snack bar, we seem to see a range of snacks: pizza, coxinha, pastel, esfiha, … Each one is made from the same grain. Hiding behind the diversity of options offered to us there’s a food monotony, which only serves industry. The more homogenized our habits, the easier products flow across the globe. But this means we’re threatening several endangered species. By paying homage to the plant kingdom, we recognize and reclaim the enormous biodiversity at our disposal, not just benefiting our own health, but that of the whole planet. So we suggest that our menu isn’t read according to what’s been left out. We avoid expressions like “no meat”, “no dairy”, etc. It isn’t about leaving things out, but abundance and regenerating biodiversity. The meat and dairy industry, above all in Brazil, needs to be scrutinized more closely. If I know 90% of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest is caused by farming, how can I take the decision to put milk in my coffee just because “I like it”? We urgently need to look at food as more than a matter of personal taste. Just as much, our eating habits are a collective, environmental, cultural, historical and social matter. In terms of any potential frustration from the public at a plant-based menu, again, we’re not talking to the public as consumer, and that’s why the restaurant isn’t focused on a posture of “client satisfaction”. This restaurant is an invitation to politicize our palate and become conscious of the environmental impact of our habits, as part of an event that has deeply ecological motivations. Our assistants are also the work’s educators. We have brought in an ecogastronomy school as partners. The work is concerned about education. We address personal taste, not only looking for tastes and edible landscapes that interest the palate and our sense of aesthetics, but that also address the hunger for biodiversity, the hunger for a fairer relationship between farmer and consumer, the hunger for more forests, the hunger for cleaner rivers, the hunger for less urban violence and so many other hungers frustrated by a simplistic attitude to the food we eat.

The concept of the work is for visitors to have access to every process involved in each type of food, from how it’s grown to how it’s prepared. How will you do this?

JMB: We’ve set up an educational structure: we’ll have workshops and conversations with farmers; we’ll make recipes available, have cookery demonstrations. Our educators are also on hand to engage the public’s questions on all of these processes. We’ve also been careful not to create an atmosphere overcharged with information. Instead, the atmosphere will be welcoming and if the public just want to have a coffee and not learn anything about the project, that’s fine. Our educators have been trained to respect each person’s own hunger. If someone’s interested, they’ll be able to find out more. If not, at least they’ll know the coffee they’re drinking was grown in an agroforest and their body’s cells are being stimulated by highly concentrated forestness. Some messages are communicated beyond speech in this way and come through the experience itself. What if our body’s cells are aware the food was grown free of pesticides, that it carries the forest in every molecule of its makeup? We believe it can.

How will the restaurant work day to day?

JMB: We thought it important that as well as reflecting on food in a wider context, the eating experience should also translate concepts from agroforestry systems. Agroforests are cultivated in layers. Each tier captures a different ray of light. For example, coffee likes being in a darker layer. And because the avocado tree likes more light, it lives in layers higher up. So we thought how we could translate this vertical experience to the act of eating and arrived at food in jars. We were inspired by those landscapes made of sand between two glass frames, imagining that building up each jar could also use the glass’s verticality, evoking the image of a layered landscape. So our dishes are organized in layers and called “landscapes”, hinting at the relationship between what we eat and where the food came from.

You have already mentioned a food activism workshop. What’s your relationship with this topic? When did you start to become interested? Have you already had other experience with food? What is your relationship with eating?

JMB: I’ve researched the relationship between the work of art and the place they’re installed for more than 20 years. In art, we call these practices site-specific. This has been the subject of my research both as an academic and as an artist. These practices first appeared in the 1960s and 1970s, as part of a wider environmental awareness movement and a change in Western thought that included the feminist, student, gay liberation and ecological movements. In site-specific practices, the place of the artwork’s installation is not a mere support for an artistic gesture, but a place whose specificities help to define what can be constructed there. In this sense, the space abandons this passive state to become an actor in creating the work. And the artist’s role, beyond self-expression, is also one of listening and recognition of local specificities: not just architectural questions, but the flow of people, history, environmental questions, etc. I call this “listening to a space” and this movement is part of a way of working that sees the work as a system, rather than being just an object installed in a determined place. For example, this same period also includes experiments in land art, which are works constructed directly in the landscape. In 2011, while I was writing my PhD thesis on this, I began to notice how my eating habits affected my writing. Writing a thesis is a long and lonely process that makes us more attentive to moods and sensations, as it reduces the number of stimulations from our surroundings. So I began to experiment, observing how my body behaved in relation to what I was eating. I often joke that I was writing my thesis with my right hand while my left hand researched nutrition. It didn’t take long for me to arrive at topics such as veganism, raw foodism, agroecology and food activism. As I deepened my research, I began to realize that the two subjects weren’t as disconnected as I’d imagined. Above all in the literature on agroecology in English, I began to come across words like site-specific and context-specific to describe this line of thought. This new linkage made me seek out authors writing on the topic, understanding food as a privileged intermediary between the society and environment. Translating this to artistic thought, I began to think that, by being an intermediary between individual and place, food and its growing practices could be understood from an artistic perspective. For example, how can we think of the performativity of the act of eating, considering how what we eat defines the landscape we live in? So instead of just recognizing this impact, how can we add a degree of intentionality for this impact to be not just a side-effect, but a goal to remodel the planet? This is when what I call “environmental sculpture” was born that I developed in my postdoc research in 2014 and have been using to define my work, such as Restauro. This is where the concept of imagining our digestive system as sculptural tools comes from. In terms of my own food, I have been enthusiastic about plant-based nutrition since 2011.

How did you have to modify the restaurant at the Biennial for the project? How did you put the menu together?

JMB: Yes, the space on the mezzanine where the restaurant is located was conceived together with Grupo Inteiro, a collective of artists and architects I’ve worked with many times. They came up with the structures working as screens that create what we call the space’s “microclimates”, where visitors can eat, read, listen to the sonic landscapes we recorded or simply relax. The menu was created with a number of drivers. The most important is seasonality. We contacted our farmers to find out what would be in harvest between September and December. With this knowledge we created recipes that always have a lot of leeway for adaptations. For example, we don’t use the concept of mashed potato. Our recipe for mash uses “root vegetables” so it can be adapted to what the farmer can offer. So the farmer in no longer just a supplier of something we planned in advance, but cooperates in the process or even becomes a protagonist in the relationship. By inverting the logic of supplying a conventional restaurant, where fixed recipes determine what the farmer produces regardless of season or even the unforeseen obstacles that always happen in farming, I want “the earth to determine what we eat”. This phrase was inspired by the artist Robert Smithson, one of the pioneers of land art and site-specific practices, who said that he let the place determine what he would build. Despite this whole conceptual approach to the menu, it’s important that our meals are pleasurable, tasty and “agridelicious”, a term we made up to play with the idea. Neka Menna Barreto, an organic farming enthusiast, is our fairy godmother and makes the food shine so it gives pleasure, whether in terms of aesthetics, taste, texture, inventiveness, consistency and all the attributes of delicious food that—beyond its harmony with the environment—also gives pleasure.

Gastronomy is receiving ever more attention from readers and viewers. How has this attention changed our relationship with food in your opinion?

JMB: From what I see of gastronomy, although I’m not an expert in the field, there is an enormous emphasis on our palate and our taste buds. Food is still too centred on the mouth and the momentary pleasure food gives us, making it an easy prey for the “awe-inspiring” products industry produces. On the other hand, I have followed the efforts of chefs and other initiatives that aim to make the eating experience more complex. Although I think we need to go further in this sense, given how urgent the environmental damage is that our habits have caused.

What was the role in the work of Neka Menna Barreto and the Escola Como Como de Ecogastronomia, part of the Slow Food Movement in São Paulo?

JMB: Neka Menna Barreto and the Escola Como Como are contributors to the project, have developed the menu and will manage the kitchen. The Escola Como Como was responsible for bringing the concept of ecogastronomy, which has a lot to do with what we want to discuss. It’s an approach to the art of gastronomy that goes beyond the palate, embedding food in the complex field of relationships involving how food is grown, its environmental impact, its relationship with work and impact on our health. In other words, seeing food well beyond its predominant position as merchandise. I see ecogastronomy as a way of addressing a type of hunger that is more than just physiological, but is a hunger for fairer labour relations, a hunger for biodiversity, a hunger for cleaner air, to support smallholder farmers, to reduce violence in our cities, to be able to feed life as we feed ourselves. Most of the food we consume today only addresses nutritional value. A balanced diet takes into account the amount of vitamins, proteins and carbohydrates in a dish. But food is multidimensional and we need to be more conscious of where it came from, how it was grown, the conditions the farmer lives in, how it was transported. This pattern needs to be redesigned, restored. This is all is invisible in the current system of food production. A plate of meat covers up the deforestation involved in its production, for instance. It is quite ridiculous that a nutritional table only analyses food in terms of calories, minerals and vitamins. How can we create more complex images for what we eat? Ecogastronomy addresses this theme maturely and responsibly, understanding food as the main intermediary in the relationship between society and the environment, between human beings and the earth, a position also held by Restauro.